Artist Spotlight: Mark Rothko

Andrea Duffie

Author's note: It's been a crazy past few weeks. A last minute trip to Seattle and lots of things going on at work have made it tough to produce a blog post on a regular weekly basis. But I'm hoping to get back in the swing of things soon!

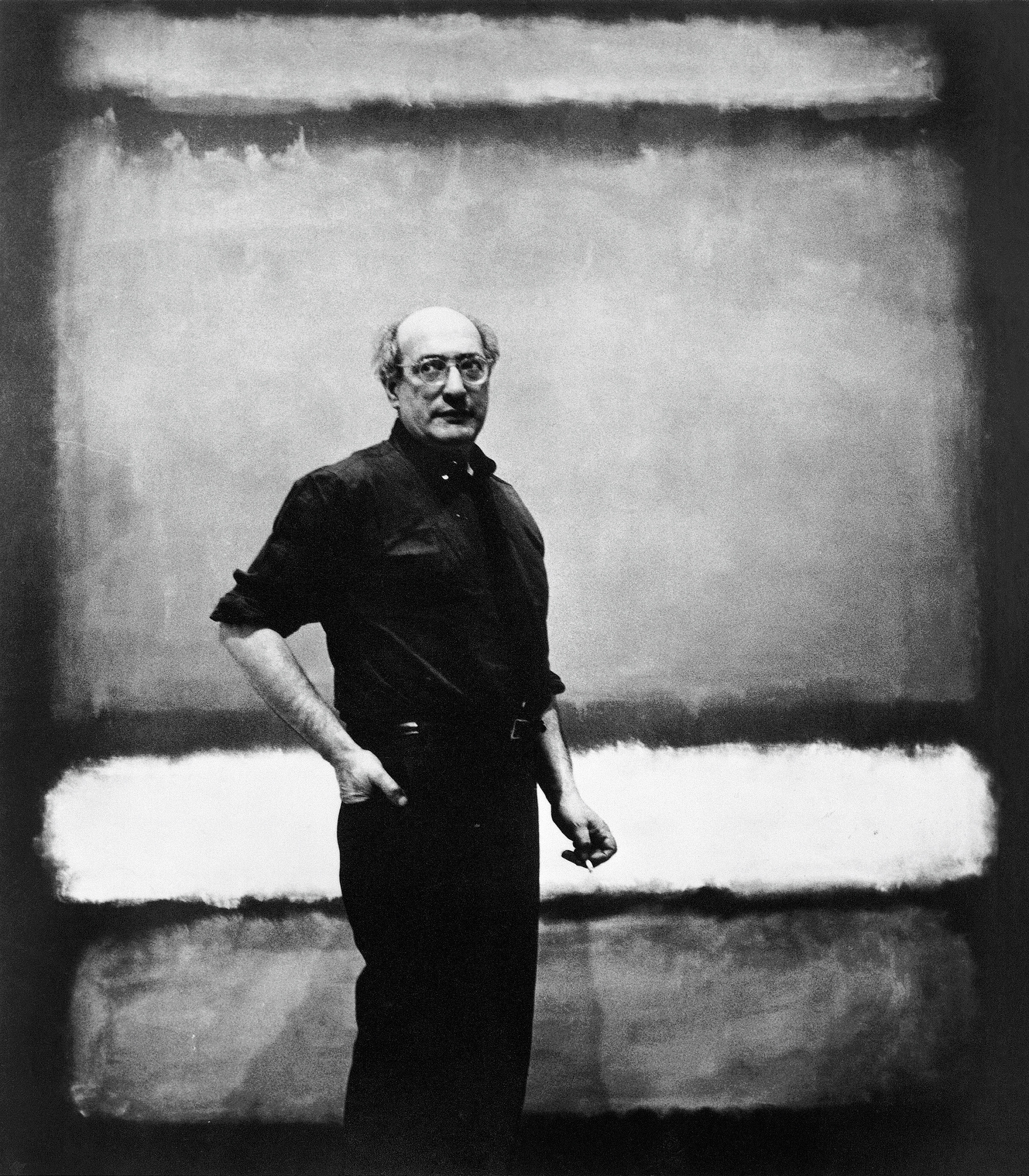

Mark Rothko

I've been on a Rothko kick lately.

Perhaps it's because, aesthetically, I really like how elemental his multiform paintings are. I enjoy the different ways that the color combinations interact with each other, how the painted edges interact with the edges of the canvas, how one shade fades into the next.

I find Rothko's work soothing and interesting to look at. I find it fascinating how the various colors and effects all come together to form a whole, to set a mood.

And with that, here's an artist spotlight — based on five facts that I find incredibly interesting — about Mark Rothko.

1. MARK ROTHKO = MARKUS YAKOLEVICH ROTHKOWITZ

While Mark Rothko's work was associated with Abstract Expressionism — the first-ever art movement specific to America following the fallout of WWII — the artist himself was an immigrant from Russia.

Markus Yakolevich Rothkowitz arrived at Ellis Island with his mother and his sister in 1913, joining his father and brothers who had already immigrated to the U.S. The family settled in Portland, Oregon.

Markus became a U.S. citizen in 1937, prompted by the rise of Nazi Germany and the fear of a sudden deportation of American Jews. In 1940, when he was 37 years old, he changed his name from Markus Rothkowitz to Mark Rothko.

The Rothko Room at the Phillips Collection, featuring Green and Tangerine on Red (1956), Ochre and Red on Red (1954), and Green and Maroon (1953). Not pictured: Orange and Red on Red (1957).

2. ROTHKO RAN WITH AN ARTSY CROWD.

Rothko spent a lot of time around a who's-who of Modernists — individuals who already were, or who would soon become, celebrated artists in their own right:

• While a student, he took classes with Abstract Expressionist painter Arshile Gorky and was mentored by Cubist painter Max Webber in New York.

• While teaching in New York, he met Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Joseph Sloman, John Graham, and was mentored by Milton Avery.

• He developed a close friendship with Abstract Expressionist Clyfford Still, eventually teaching a class with him at the California School of Fine Art along with David Hare and Robert Motherwell.

However, many of Rothko's artist friends became jealous once his later paintings started bringing him more critical acclaim and financial success. As a result, Rothko's relationships with Newman and Still became particularly strained.

Mark Rothko, 10 (1952) at the Seattle Art Museum

3. MYSTERY MATERIALS

For a long time, science was baffled as to what Rothko put in his paints that allowed his works to achieve such a luminescent quality. But thanks to the Tate Modern and MOLAB (an Italian organization that provides technical support to European conservation projects), the mystery has been solved.

It turns out that Rothko would often modify his paints with a variety of unusual materials, which would all affect the paint's color, texture and drying time. These materials included egg, glue, and several different kinds of resin which increased the viscosity of the paint, making it easier to spread without dulling its color.

Rothko also constantly experimented with different mixtures and layering sequences, applying phenol formaldehyde to his works to keep the layers from blending into each other — a technique which created much of his works' vibrant colors.

Mark Rothko, No. 61 (Rust & Blue) (1953) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA)

4. FILLING THE SPIRITUAL VOID

Rothko had a tumultuous relationship with religion throughout his life. He grew up in an Orthodox Jewish household, which meant that his early years in Russia exposed him to the violence and cruelty of the country's anti-Jewish pogroms. When his father passed away after the family's first few months in America, Rothko mourned him at a local synagogue for a year before vowing never to return.

However, the artist remained active among the Jewish community and was a staunch political activist. His time as a student of Max Webber, another Russian-Jewish artist, led Rothko to see art's potential as a tool for emotional and spiritual expression.

By the time Rothko's "multiform" painting experiments had matured into his signature style, he was still flirting with larger spiritual concepts in his art. He spent years studying Nietzsche's writings on mankind's spiritual void, and Jung's work on archetypes as a way to transcend culture and language to a greater collective consciousness.

Rothko's work was now about creating intimate, spiritual experience between the painting and its viewer, for which color was merely an instrument. In his words, Rothko sought to express "basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on...The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them."

His work finally culminated in the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. Rothko's final paintings were dark, monumental works in deep reds, browns and black, several of which were arranged in a triptych style usually associated with Roman Catholicism. Inside of the chapel, they surround viewers with massive, imposing visions of darkness, transcending specific religious faiths and symbology in order to create a contemplative and deeply individual spiritual experience.

Personal favorite: Mark Rothko, No. 14 (1960) at SFMoMA

5. ROTHKO'S DEATH CREATED A SERIOUS LEGAL MESS.

Rothko committed suicide on February 25, 1970, following health problems, a divorce, battles with alcoholism and bouts of depression.

However, prior to his death, Rothko had wavered on what he saw as the purpose of his artistic foundation — the governing body that would handle his estate and control his legacy once he was gone. As with most artistic foundations, its original intent was to parcel out Rothko's work to institutions and collectors who would honor the intentions of the artist's work. But before his death, Rothko had been thinking about the foundation being more of a charity, its purpose to create grants for older, less successful artists.

This intent for the foundation because very important when, three months after his death, the executors of Rothko's estate sold off 100 of the artist's paintings at rock-bottom prices — roughly $12,000 each — to Marlborough Art Gallery, at a time when such paintings were regularly worth at least $50,000 on the open market. Marlborough turned around and sold the paintings for at least $180,000 per painting, all while the executors of Rothko's estate had mysteriously found opportunities to become more actively involved in the gallery: one executor was named director of Marlborough merely five weeks after Rothko's death, another became part of the gallery's stable of artists.

What followed was a legal cluster that shook the New York art world: the executors of Rothko's estate were accused of self-dealing and conspiring to defraud the estate, while Rothko's two children sought to nullify the sales and claim half of their father's estate under New York law (despite their being written out of the artist's will.)

The debate was complex: If the Rothko foundation was, as originally intended, meant to secure Rothko's works in museums and with collectors, then the estate executors had seriously undercut the interests of the foundation — and created a perceived conflict of interest to boot — by selling everything off. However, if the Rothko foundation was remaining consistent with the artist's later, more charitable thoughts for the organization, it would have made perfect sense for the executors to sell off the works to create money that could then be parceled out as grants.

The entire story is fascinating, and can be explored more fully in an online article by David Levine, "Matter of Rothko".

Mark Rothko, Orange, Red and Red (1962) at the Dallas Museum of Art