A Few of My Favorite Things: Collection Highlights from San Francisco's Asian Art Museum

Andrea Duffie

San Francisco's Asian Art Museum is the largest of its kind in the country, so I was particularly excited to visit during my #Museumpalooza a few weeks ago.

However, I know next to nothing about Asian art. Like many art historians, my artistic education (with the exception of one course in grad school) has had a prominent Western focus, which I am slowly trying to correct.

That said, the Asian Art Museum was EXACTLY what I needed, because it provided just enough context for me (and/or other less-than-knowledgable viewers) to get a grasp of a gallery's time period or subject matter without coming across as "too wordy" or "too academic".

As a result, I left the Asian Art Museum realizing how much there is about Asian art that I don't know. Most importantly, the museum's approach made me want to go back and learn more, and that's the crowning achievement for any museum in my book.

Here's a rough list of the Top 5(ish) Coolest Things I Saw:

1. INTIMIDATING RELIGIOUS DEITIES

Simhavaktra, China, Qing Dynasty, 1736-1795.

Simhavaktra, also known as "the lion-headed one", is a magical being that inhabits the sky. Her hair blazes upward with the fire of wisdom, and her lion head represents fearlessness.

She also looks pretty badass, which is one of the things I really enjoy about representations of Indian and Chinese deities: so often, they look like gods you just don't want to mess with.

The Buddhist deity Achala Vidyaraja (Japanese: Fudo Myoo), 1100-1185. Japan, Heian period.

Speaking of gods you just don't want to mess with, let's not forget about Japanese deities. Fudo Myoo, known as "the immovable one", is one of the Five Bright Kings in Japanese Buddhism. Fudo is a manifestation of the central cosmic Buddha, which means his job is to protect Buddhism and its true adherents. This is a serious job, so Fudo has his game face on – complete with sword, rope, and giant flame, the latter of which he uses to purify evil.

2. COOL SCROLL PAINTINGS

Dong Shouping, Red plum blossoms, Chinese, 1983.

On a less-intense note: Over the past few years, I've started developing a soft spot for Chinese and Japanese scrolls and silk screens. I absolutely adore their level of detail, and how "soft" they seem (tonally and stylistically) compared to the modern/Western movements I'm more familiar with, like Abstract Expressionism.

But it's also fascinating to see how exposure to those movements affected those artists practicing the older tradition. Take the blurred, blotty abstractions of the branches in this Red plum blossom work on paper, which was made in the 1980s: traditional scrollwork is very precise, so the bits of abstraction here are a radical divergence from the older style.

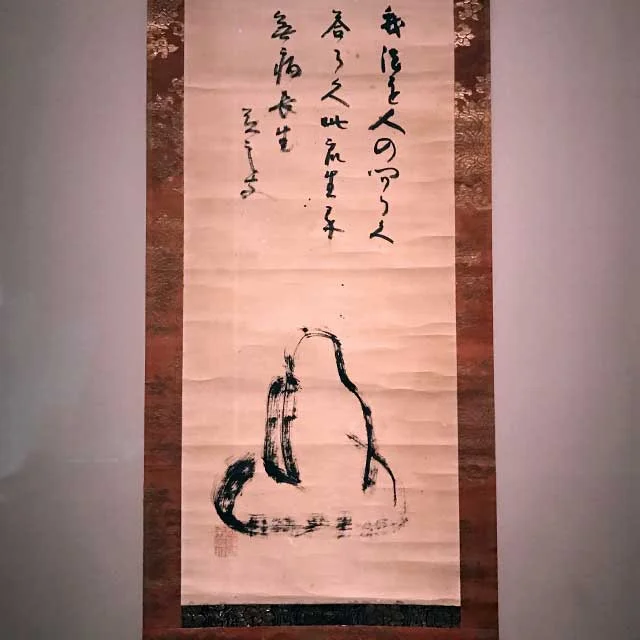

Jiun Onko, Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma) facing the wall. Japanese, Edo period, 1615-1868.

I also enjoyed seeing this "wall-facing Buddha", which is apparently a motif throughout Asian art that I'd never come across before. According to one story, Bodhidharma, the very first patriarch of Zen Buddhism, sat in silent meditation in front of a cave wall for nine whole years. (That is a special kind of patience and focus that I do not have.)

This particular story is usually artistically represented with as few strokes as possible – simplicity of form above all else. The above example by Jiun Onko only uses three dry strokes.

Masako Takahashi, Black Enso, 2014.

Speaking of "simplicity of form", one of the most common images in Zen Buddhist art is the enso, a circle that is drawn with a single brush stroke. But Masako Takahashi's contemporary enso isn't a white brush stroke on a black surface – it's a print of a high-resolution scan of the artist's own hair, which adds an element of personalization to this very symbolic work.

(Of course, beneath the contrasting colors and peacefulness of this image, somewhere in the back of my mind it reminded me of The Ring, which is coincidentally something that also originated in Japan.)

3. FASCINATING KNICK-KNACKS THAT WILL OUTLIVE US ALL

Ritual vessel in shape of a rhinoceros, China, Shang dynasty, 1100-1050 BC

This adorable little guy is over 3,000 years old! Other artifacts show that rhino hunts – the capturing of rhinos for sacrifice during rituals – were major events during Bronze Age China. The statue has an inscription on the bottom that provides firsthand account of society during the Shang dynasty.

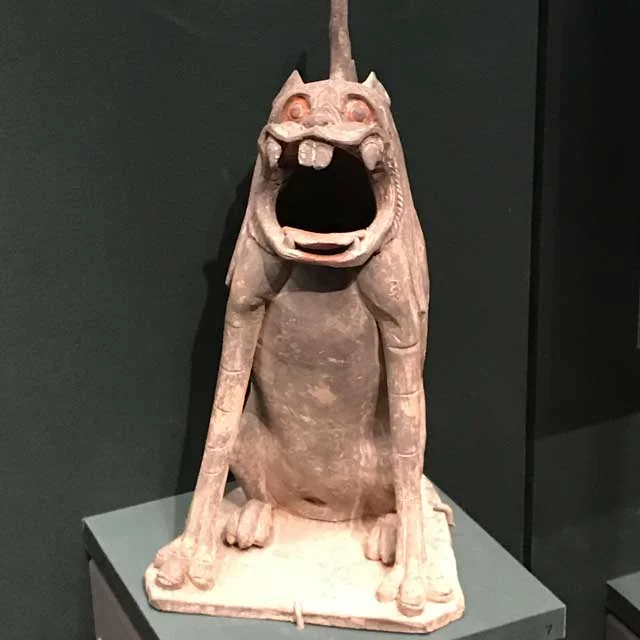

One of a pair of spirit guardians, China, approx. 500-535

GASP! This critter is a spirit guardian, a popular motif in Asian art. It would have been placed outside the door of a tomb or sacred place, to scare off unwanted visitors.

Buddha dated 338. China; Hebei province.

Hailed as one of the "treasures" of the Asian Art Museum, this gilded bronze Buddha is the earliest known Buddha object produced in China, with an inscription on its base that references the year 338.

Let that sink in for a minute: "Earliest known Buddha object produced in China". A date that occurs 500 years after Buddhism was imported from India to China, in roughly the second century BCE.

This little Buddha has seen some things over the past 2,000+ years.

Another cool fact about this statue is that, as the saying goes, "all that glitters is not gold". This statue is actually made out of bronze, gilded (painted) with a thin layer of paste made out of gold and mercury. The bronze figure would have been heated over a fire to evaporate the mercury, leaving the gold bonded to the surface.

4. ANCIENT BADASS WEAPONRY

Indonesian daggers, approx. 1850-1950. Two are made from steel, iron, wood, and brass; the other includes whalebone and copper.

Back in "the old days", many Malay and Indonesian men wore a kris, or dagger. While kris are mostly used for ceremonial purposes these days, some are revered for their symbolic associations for turning away flames or floods, or flying through the air to their master's defense.

The blades are usually formed of several layers of red-hot steel, layered on top of each other and pounded thin, before being treated with acid to bring out the intricate patterns resulting from the repeated folding and pounding of its creation. Krises have either wavy or curved blades, and collectors can often recognize which area or island each handle, blade or fitting comes from.

5. ATTACK OF THE MONKEYS

Scene from the epic Ramayana: Kumbhakarna battles the monkeys, approx. 1075-1125. Cambodia or northeastern Thailand.

I have no familiarity whatsoever with the Indian epic of Ramayana, but I think I might need to pick it up, because it sounds awesome.

Evidently, in part of the story, the wife of our hero Rama is cruelly abducted by Ravana, the demon king of Lanka. Rama got the local monkeys to join him in his assault on Lanka, to go get his wife back...which sounds like the kind of thing that would make for some badass cinematography today:

At least they're not throwing...stuff. Or using guns, like whatever version of Planet of the Apes Hollywood is on now. (Copyright Walt Disney Pictures)

Too bad that in the Indian epic, the monkeys don't win. The demon king's brother, Kumbhakarna, kicks some monkey ass, maiming and devouring them by the hundreds. (RIP monkeys.)

Finally, Rama himself joins the fray and cuts Kumbhakarna to teeny tiny bits, thus ending the battle and the needless waste of monkey life.

Big thanks to Asian Art Museum for an awesome afternoon, and for inspiring me to learn more about all the awesome stuff in your collections!